Queen's in the Middle East

Winter In Iraq

From Suffolk 169 Brigade entrained on the 24th August 1942 and embarked at Liverpool next day for an undisclosed destination. The 2/5th and 2/7th Queen’s with Brigade Headquarters, commanded by Brigadier L.O. Lyne, and the 113th Field Regiment RA embarked in the MV Johann van Oldenbarnvelt, a fairly new and spacious Dutch liner, but inevitably very crowded on the troop decks. The 2/6th Queen’s with Divisional Headquarters were in the SS Franconia, an older and smaller ship, where conditions were not nearly as good. Both ships left Liverpool on the 27th, but sailed only as far as the Firth of Clyde, where a convoy of nineteen ships with an escort of a cruiser and five destroyers assembled, which finally left home waters on the 28th. Bad weather was encountered at once and there was much seasickness. However, when everyone had their sea legs, useful training was organised, as is usual when trooping, and on the Johann van Oldenbarnvelt companies were even able to carry out a daily one hour march on the wide decks. The convoy called at Freetown, but troops were not allowed ashore. It then sailed direct to Cape Town uneventfully, but a Liberty Ship, the Ocean Flight carrying most of the Division’s transport and guns, sailed unescorted and was torpedoed and sunk by a U-boat. Fortunately the 54 men on board took to the boats and managed to reach the Gold Coast safely, but the loss of this ship was to result in considerable inconvenience, and rendered the Division temporarily non operational.

The convoy reached Cape Town on the 25th September and received the usual enthusiastic welcome from the warm-hearted inhabitants. On the Sunday detachments of the 2/5th and 2/7th Queen’s marched four miles to the Cathedral for a church service, the last proper church which units were able to attend for many months to come, However, plans had to be altered because of the loss of the Ocean Flight, and all the transport officers and men of the Brigade were detached and arrangements made for them to go to Egypt to take over new transport to complete to scale. Such transport that was still with the units in the convoy had to be reallocated thinly throughout the Division. The Commanding Officers were informed that the destination of the 56th Division was Iraq, and the ships carrying divisional personnel joined another convoy for Bombay, which anchored off that port on the 16th October. Two days later 169 Brigade disembarked, the 2/7th Queen’s remaining in Bombay in the pleasant Colaba Camp, whilst the other two battalions moved to the big transit camp of Deolali.

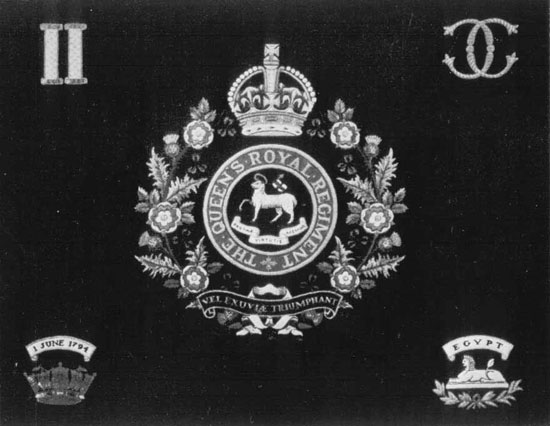

The Regimental Plaque.

The 2/7th Queen’s was first to leave Bombay on the 25th October in the Dutch ship Nieuw Holland, with the 9th Royal Fusiliers of 167 Brigade also on board, which meant that this small ship was very crowded. They arrived at the mouth of the Shatt el Arab on the 30th, disembarking next day at Margil before being sent by train to 39 Rest Camp at Zubair, a tented camp in semi-desert.

The 2/5th and 2/6th meanwhile had remained twelve days at Deolali, where it was hot and dusty with little to do. On the 31st October both battalions, glad to get away from this unpleasant camp, returned by train to Bombay, and, with 113 Field Regiment, embarked next day in the Rajula, a small but pleasant ship, which took them through the Shatt el Arab straight to Basra, where they disembarked on the 13th November.

The Brigade then moved by train via Baghdad to its final destination in the foothills of the Kurdistan mountains about 13 miles north of Kirkuk, with the 2/7th again leading the way on the 15th and followed on successive days by the 2/5th and the 2/6th. Two nights were spent in the trains, and an otherwise monotonous and uncomfortable journey was broken by a halt at Baghdad. The railways running north and south from Baghdad are of different gauges and several miles apart, so this involved a march across the River Tigris through the city, which appeared to be squalid and smelly. The trains were unheated, and the nights extremely cold, so it was fortunate that winter clothing had been issued in Basra, where at this time of the year it was still hot and dusty. On arrival the battalions found that the camp areas were just expanses of desert without amenities of any kind. For the first few weeks everyone concentrated on trying to make the camps fit to live in. A drainage system had to be constructed, and cookhouses and latrines built. When it rained it was very cold and muddy, and, to keep out the cold, tents were dug down to three of four feet. Timber and other materials were at a premium.

The transport column arrived about a fortnight after the battalions, having driven overland from Suez across the deserts, and experiencing several sand-storms along the way. Eventually some intensive individual training was started, including training with mules, which many found to be an adventurous experience! Football, rugger and hockey grounds were constructed nearby, and games indulged in with enthusiasm. Recreational journeys were made to Kirkuk, where there were ENSA entertainments and a good supply of cheap local wine and a powerful arak. Nomad bands were often seen in transit near the camps. Thieving was one of their recognised pastimes, and stringent action had to be taken to safeguard weapons and belongings. Three sergeants of the 2/7th had the undignified experience of waking up to find no tent over them and no clothes to wear! By the time the tent was recovered it had been made into several pairs of Kurdish trousers. Eggs and dates were local delicacies which could be obtained in great profusion, providing the basis of some good suppers cooked on improvised petrol fires.

At this time the Tenth Army, of which 56th Division now formed part, came under the Persia-Iraq Command (Paiforce) with responsibility for sustaining the flow of aid to Russia via the Trans-Persia Railway, and in readiness for any threat in the event of the Germans penetrating the Caucasus during their 1942 summer offensives. The German plans for 1942 envisaged the principal offensives taking place on the southern fronts with a view to outflanking the main Russian concentrations which were positioned to defend Moscow and Leningrad. Hence, at the northern end of these offensives, Stalingrad would be a key objective before the Fourth Panzer Army swung north to get behind Moscow by following the line of the River Volga, whilst the southernmost thrust by Army Group A was aimed through Rostov-on-Don into the northern Caucasus in order to capture the oilfields of Grozny, and then ultimately the major oilfields of Baku on the Caspian coast. Had these plans succeeded in their entirety, then the way into Persia and to the even richer oilfields of the Persian Gulf would have been a real possibility for German endeavours. Furthermore, if Novorossisk and Batum were to be captured by the Germans, the Russian Black Sea Fleet would be forced into internment because of the lack of base facilities.

Persia had been occupied by joint British and Russian forces in August 1941 following the German invasion of Russia, in order to eliminate the successful infiltration into that country of German diplomats and military advisers. At first resistance from Persian forces had been met, but by the end of August the Persian government had decided to cease resistance. There followed a period of intense diplomacy since the British government, in particular, with large British economic interests in the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, had no wish to hold down an antagonistic population with a permanent army of occupation. In September the Shah was persuaded to abdicate in favour of his gifted twenty-two year old son, and the new Shah, on Allied advice, restored the constitutional monarchy, whilst his father went into comfortable exile in South Africa. All Germans were expelled from Persia, which declared its neutrality, but the Allies were permitted to use Persian communications for the transit of war supplies to Russia. The Trans-Persia Railway was placed under American management with American personnel, military and civil, with an assurance that it would be brought up to modern standards, which would be handed back intact at the cessation of hostilities. Finally, most of the British forces withdrew from the country, leaving only detachments to guard communications, and Tehran was evacuated by both British and Russian troops on the 18th October 1941. Unfortunately, the Russians insisted on keeping five divisions crammed into the north of the country, a constant cause for complaint and friction with the local population.

The arrival of 56th (London) Division coincided with the high-tide of German penetration into Russia. By the 18th November 1942 only one tenth of Stalingrad remained to be taken to complete its capture; Novorossisk had been captured, to leave Batum as the only naval base available to the Black Sea Fleet; and the panzers were only about 25 miles from Grozny. The spectacular advance of Army Group A throughout the summer had forced General Sir Henry Maitland Wilson, C-in-C Paiforce and GOC Tenth Army, to order the preparation of defences to cover the route of the railway between Tehran-Baku. For diplomatic reasons he could not send in Tenth Army formations, but reconnaissance parties were sent from Iraq in order that they could see the area in which they might have to operate and to inspect the work that had been carried out by contractors. In early December, therefore, the Commanding Officers and Adjutants of 169 Brigade, with the Brigade Commander and his staff, proceeded to Khanaqin, and from there followed Major General ‘Bill’ Slim’s route into Persia with his 10th Indian Division during his short campaign 15 months previously. They visited the Pai-Tak Pass, where Slim’s forces had conducted operations, and spent several nights at Kermanshah, the area allocated to the Brigade in the event of an advance into Persia. Some of the scenery was magnificent, and confirmed that defending forces, if resolutely handled, were likely to have a distinct advantage over attackers, especially as the air support available was expected to be robust.

However, although not discernible at the time, the crisis had already passed. On the 19th November the Russians struck back at the German Sixth Army at Stalingrad and by the 23rd General Paulus and his army were cut off. Although he held out until the 31st January 1943, Paulus signed the surrender of his army and became a captive together with almost 120,000 of his men. At the end of December the Russians also started their winter offensive against Army Group A in the Caucasus, with the opportunity of destroying another 400,000 men, but they were thwarted by Colonel-General Ewald von Kleist, who, although completely isolated, conducted a brilliant winter retreat to the Kuban Line, which he held against all attempts to break it until September 1943, when he was finally allowed to evacuate it across the Straits of Kerch to the Crimea.

Despite these potential successes for the Allies, after Christmas the scale and intensity of training in 169 Brigade increased, with rigorous battalion exercises followed by higher formation exercises throughout January. The culmination of this training was Exercise ‘Fortissimo’ in which 169 Brigade carried out a full-scale attack under cover of a barrage with live ammunition fired by the divisional artillery, machine-guns and mortars, watched by 5,000 spectators of many nationalities. It was a most impressive demonstration and an excellent battle inoculation for the Brigade.

During February a party from 56th Division was sent to join the Eighth Army to gain battle experience, since it was now evident that there was little likelihood that the Tenth Army would be seriously deployed in Persia. The party consisted of 25 officers and 40 warrant officers and sergeants of the various divisional units under Lt Col J.Y. Whitfield, the Commanding Officer of 2/5th Queen’s. They were taken by MT across the deserts to Alexandria, and there embarked to be taken by ship to Tripoli, joining the 4th Indian Division on the 31st March a week prior to the battle of Wadi Akarit. Everyone in the party was sent to an opposite number in a unit of his arm, which involved many taking part in the battle itself. The party actually incurred eleven casualties before a halt was called and the survivors were taken away from their attachments! It was a wonderful experience, but one not to be repeated so realistically again.

« Previous ![]() Back to List

Back to List ![]() Next »

Next »

Related